Max van der Werff, which in English translates as Max from the Wharf, is my name.

Curiosity killed the cat, but keeps me alive. Investigating things is my hobby.

Since I started the Dutch War Crimes project people ask me questions like: “why are you so obsessed with this subject?”

Let me try to explain:

Atjar Tjampur, from Malay: Atjar = sour vegetables, Tjampur = mixed

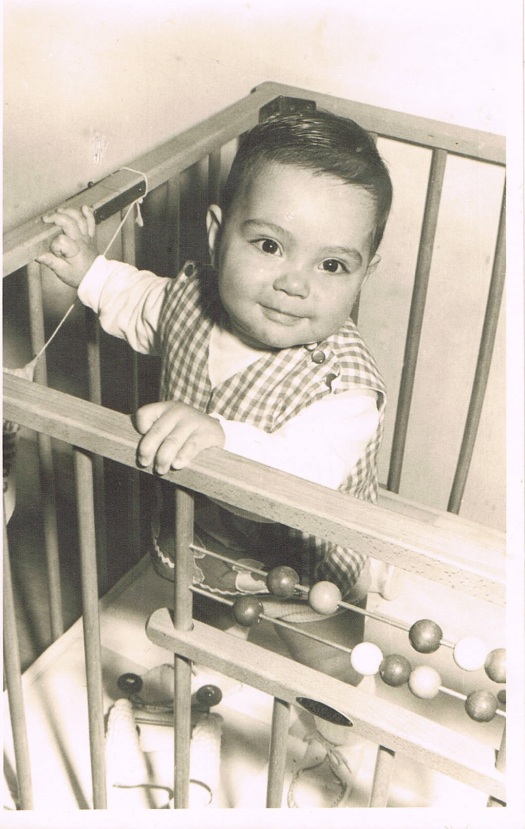

This is me in 1964: Belanda = Dutchman, Tjampur = mixed

Here’s my mom and dad at their wedding in 1961

Here’s my mom and dad at their wedding in 1961

Anne Merlijn, born in Apeldoorn, Netherlands

Max van der Werff Sr., born in Cilacap, Java, Indonesia

My brown and white grandparents

My brown and white grandparents

Brown: Nelly Roumimper and Bert van der Werff

White: Gerarda Theunissen and Willy Merlijn

My son Sjors as a little child made a distinction between his grandfathers. One he called ‘my brown granddaddy’ and the other ‘my white granddady’. I thought this was rather cute and so I chose to use his terminology.

What struck me is that unconsciously I put my white ancestors on the left and the brown on the right side as I photoshopped the two together. Could I have a racist bias without realising it myself?

Atjar Tjampur is a one of the many components of Rijsttafel:

Indonesian rijsttafel, a Dutch word that literally translates to “rice table”, is an elaborate meal adapted by the Dutch following the hidang presentation of Nasi Padang from the Padang region of West Sumatra. It consists of many (forty is not an unusual number) side dishes served in small portions, accompanied by rice prepared in several different ways. Popular side dishes include egg rolls, sambals, satay, fish, fruit, vegetables, pickles, and nuts. In most areas where it is served, such as the Netherlands, and other areas of heavy Dutch influence (such as parts of the West Indies), it is known under its Dutch name.

Although the dishes served are undoubtly Indonesian, the rijsttafel’s origins were colonial. During their presence in Indonesia, the Dutch introduced the rice table not only so they could enjoy a wide array of dishes at a single setting but also to impress visitors with the exotic abundance of their colony. (wikipedia)

I’d like to see myself as Belanda Tjampur, part of a large Rijsttafel which is the Dutch multicultural society.

The Second World War

Bicycle shop owned by my white grandparents in Apeldoorn (1943)

Grandfather’s diploma ‘Bicycle Business’

One day a group of German soldiers entered my grandparent’s shop and confiscated all the bikes. Among those was the one owned by the baker who had to deliver bread and the bike was his only means of transportation.

In a bold move my grandmother went to the local Hauptmann and ordered the bicycles to be returned, especially that of the baker.

Unfortunately I cannot show you a photo of the Hauptmann’s face the moment my grandmother gave him the instructions, but fact is that the German soldiers who stole the bikes, returned them to my grandparents shop.

Then May five 1945 the Germans capitulated and for my white family the war was over.

For some the war was not over. After the liberation, the Dutch people vent their anger on the ‘moffenmeiden’ – women and girls who had had any kind of friendly contact with German soldiers. They had their hair cut off in public and their heads shaven. Often a swastika was painted on their heads and they were driven around in an open trucks.

By allowing this ‘controlled revenge’, the Dutch Military Administration hoped to avoid a ‘Day of Reckoning’, a free-for-all in which reprisals against collaborators would take place without restraint.

(Map of the Former Dutch Empire 1940)

– In the middle of the map, the Asian part of the Former Dutch Empire, now Indonesia.

– Left side: the European part, often simply called ‘Holland’.

– Right side: American part, Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles. (Netherlands Antilles are not visible on the map due to the scale)

For seventy million (70,000,000) inhabitants of the Asian part of the Dutch empire, now called Indonesia, the war was far from over.

Elementary school in Cilacap. The only photo showing my father, his older and younger brother Rudy and Tonnie. (three arrows from left to right).

Elementary school in Cilacap. The only photo showing my father, his older and younger brother Rudy and Tonnie. (three arrows from left to right).

An estimated two million (2,000,000) people in the Dutch West-Indies died during the Japanese occupation from hunger, diseases and violence. Among them three of my father’s brothers and sisters.

My grandfather was conscripted as KNIL landsoldaat in 1942, but was almost immediately taken prisoner and incarcerated for 41 month’s by the Japanese imperial Army. The Netherlands never paid him a cent for his service time. This shameful part of Dutch history is called backpay issue.

After the Japanese surrender the unimaginable difficult times were not over for most (Indo) Dutch people living in the Dutch East Indies. The prospect of Dutch rule coming back to the already proclaimed independent Republic Indonesia caused fury among many Indonesian youngsters and for many month’s anybody suspect of being Dutch or having anything to do with Dutch rule was a primary target. My father’s elder brother Rudy was one of the many thousand slaughtered during the bersiap period.

Soon 150,000 Dutch troops were sent to restore Pax Hollandia in the old colony and the main motive was to restore the exploitation of the ‘wingewest’ (area for profit) as soon as possible. The Dutch elite had the opinion that the Japanese rule over the Dutch Indies was merely a short interruption and that Dutch colonial rule would be reinstated for generations to come. This fatally wrong perception of reality led to the Indonesian war of independence lasting from 1945 to end 1949 causing hundreds of thousands casualties.

My father decided to leave for New-Guinea, a part of the Dutch empire that would become the promised land for the Indo Dutch. At least, so it had been communicated by the authorities. In 1956 my dad realised that there was no future for him in this part world and decided to leave for Holland with the Willem Ruys. Some time later he met my mom in Apeldoorn.

Indonesia is deeply rooted in the Dutch DNA. Depending on which definition used 350 years of colonial rule has caused some ten percent of the Dutch population to have ancestors born in then still the Dutch East Indies.

Broken promises from a teenager’s perspective

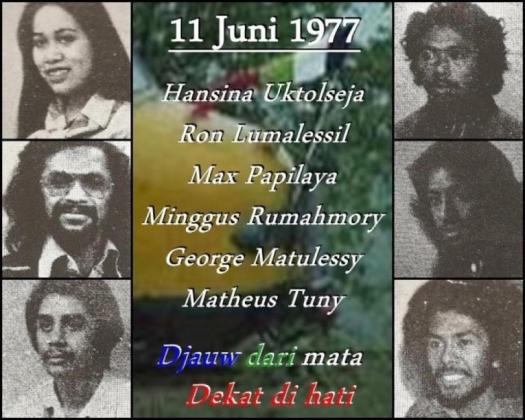

In 1977 a train was hijacked by nine Moluccans. I was fourteen years old and have very vivid memories about this event. Two years before a similar incident had taken place and the Netherlands was again hunted by its colonial past.

During the Indonesian war of independence South Moluccan soldiers fighting in the Dutch colonial army (KNIL) were promised their own independent state. This promise was never fulfilled by the Dutch government and thousands of the Moluccan KNIL soldiers were ‘temporarily’ shipped to the Netherlands along with their families. Some twenty five years later most of them still lived in barracks and some members of the second generation decided to remind the Dutch government about their promise for a free Republic of the South Moluccas.

The leader of the hijackers was Max Papilaya. His first name the same as mine and my father’s. Max. It was quite a shock. I remember my dad was very emotional in those days. Some people shouted ‘dirty Moluccan!’ at him in the street. He said that the best solution would be to ‘put them all with their backs against the wall’. He didn’t mean it. My mom countered: ‘ who is going to shoot them? You? You can’t even kill a fly’. End of discussion.

The train some days later was indeed stormed by Dutch marines. Two hostages and six of the nine hijackers were killed. Among the dead Max Papilaya.

I was shocked. My dad too. He explained to me that indeed the parents of these killed youngsters were promised their own country by the Dutch. In fact, they should not resort to violence, but the hijacking was their reaction to a broken promise.

For the fist time in my life I realised that governments lie too.

Much later I realised that Dutch society as a whole has a gigantic blind spot concerning its own colonial past. Some compare it with amnesia:

“Essentially, amnesia is loss of memory. The memory can be either wholly or partially lost due to the extent of damage that was caused.” (wikipediatric)

Amnesia cannot be the right diagnosis however, because you cannot forget what you never knew in the first place.

Some compare the attitude of Dutch society as ‘aphasia’, the inability to recognise the subject at all. Also I read about collective narcissism which would explain the Dutch finger pointing, however never in front of a mirror.

Another diagnosis: the patient suffers form post-colonial trauma and is still in a state of denial.

Then in 2011, a court case changed everything.

Rawagede Massacre

Diorama in Rawagede, now called Balongsari, West-Java

Diorama in Rawagede, now called Balongsari, West-Java

More than sixty years after Indonesia’s independence the Dutch court rules in favour of nine widows whose men were killed by Dutch troops on December 9th, 1947. Only then it became clear to me on what scale historical facts have been distorted and how incredibly effective Dutch propaganda has been.

Too serious? Maybe. Let’s end this article with a positive note. Born in Arnhem 1963, for me as a young kid Indonesia was a far away, mysterious land. Very attractive, but a little frightening too. To give you an idea about my child’s fantasy, this is a short video of the Dutch theme parc Efteling with ‘Indische Waterlelies‘.